|

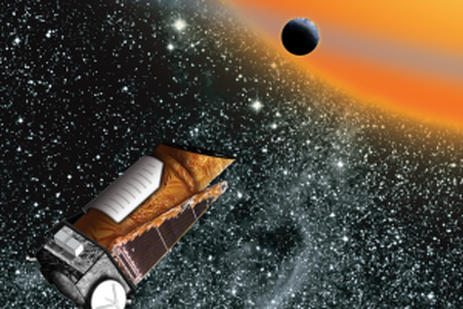

Kepler discovers 715 new planets, nearly doubling the planets known to mankind

For the first time, the vast majority of the planets found are smaller than Jupiter, including many Earth-sized planets.

For the history of human space exploration, planet discovery has been an arduous process. An object that could be a planet is discovered and then painstakingly analyzed. Until today, we knew of roughly 1000 planets, the majority of which were large, Jupiter-sized globes because their size made them easy to spot. NASA announced today that the Kepler spacecraft has added 715 new entries to our catalogue of known planets outside our solar system. And, for the first time, the vast majority are smaller than Jupiter, including many Earth-sized planets. A few are located the distance away from their sun that is considered habitable. “This is the largest windfall planets … that has ever been announced at one time,” NASA exoplanet exploration program scientist Douglas Hudgins said in a teleconference. All of the planets are located in solar systems that contain multiple planets. They orbit 305 different stars. Since its launch in 2009, Kepler has steadily been increasing the number of planets it finds each year. It has now discovered more than half of all planets ever found. Thanks in large part to Kepler, 95 percent of the planets every discovered were found in the last five years. Scientists were able to maximize the number of planets found by applying a new technique that allowed them to spot and verify 20x more new planets than normal. It’s known as verification by multiplicity, and it relies in part on probability. According to the NASA website: This method can be likened to the behavior we know of lions and lionesses. In our imaginary savannah, the lions are the Kepler stars and the lionesses are the planet candidates. The lionesses would sometimes be observed grouped together whereas lions tend to roam on their own. If you see two lions it could be a lion and a lioness or it could be two lions. But if more than two large felines are gathered, then it is very likely to be a lion and his pride. Thus, through multiplicity the lioness can be reliably identified in much the same way multiple planet candidates can be found around the same star. “What we’ve been able to do with this is strike the mother load,” NASA’s Ames Research Center planetary scientist Jack Lissauer said in the teleconference. Source: GigaOM

Liked this? Share it!

|

|

| Recaply Copy |

|